The third quarter of 2025 was wild. Michael Burry (the investor played by Christian Bale in The Big Short) revealed short positions in Nvidia (NVDA) and Palantir (PLTR), and is sounding the alarm on AI data center spenders like Meta (META). Read last week’s discussion on this here: Michael Burry’s AI Data Center Bubble Warning, and CoreWeave Q3 2025 Earnings

Meanwhile, cautious-as-ever Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A/BRK.B) bought over $4 billion-worth of one of the hyperscalers, Alphabet (GOOGL) stock (likely not Buffett’s call, he’s retiring).

What is going on?

For reference, when we say “hyperscaler” the rest of this article, we’re referring to the big data center operators Microsoft (MSFT), Amazon (AMZN), Alphabet, and Meta (aka Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp).

Let’s use Meta as an example… since it’s sold off over 20% from the high, and it (and Oracle, along with data center partner OpenAI) have been called out specifically as the two most egregious AI data center spenders.

What is depreciation? Is Meta going to get roasted?

Key to Burry and other bear thesis arguments against Meta and the hyperscalers is elevated depreciation expense related to big purchases. But before we talk depreciation specifically, what is Meta spending big gobs of cash on, exactly?

Equipment to support its fast-growing business. Revenue was $51 billion in Q3 2025, up 26% year-over-year.

It wasn’t widely known among investors until recently that Meta is far more than a social media company that sells ads. It operates one of the world’s most powerful data center networks.

When you’re a business with this kind of scale, there is good reason to own and control your own computing infrastructure. Meta does deep analytics and research on what drives user engagement, how best to target an audience, etc., so it can sell increasingly valuable ad time to marketers and small businesses.

Having end-to-end infrastructure, R&D, and end-market software helps Meta control its costs as it picks up billions of dollars-worth in new revenue every quarter.

And then of course there’s all the new AI research being done to generate new future revenue streams (improving ad-targeting algorithms with AI, researching AI super-intelligence, virtual reality stuff, etc.). That’s where Nvidia’s cutting-edge GPU-based servers come in.

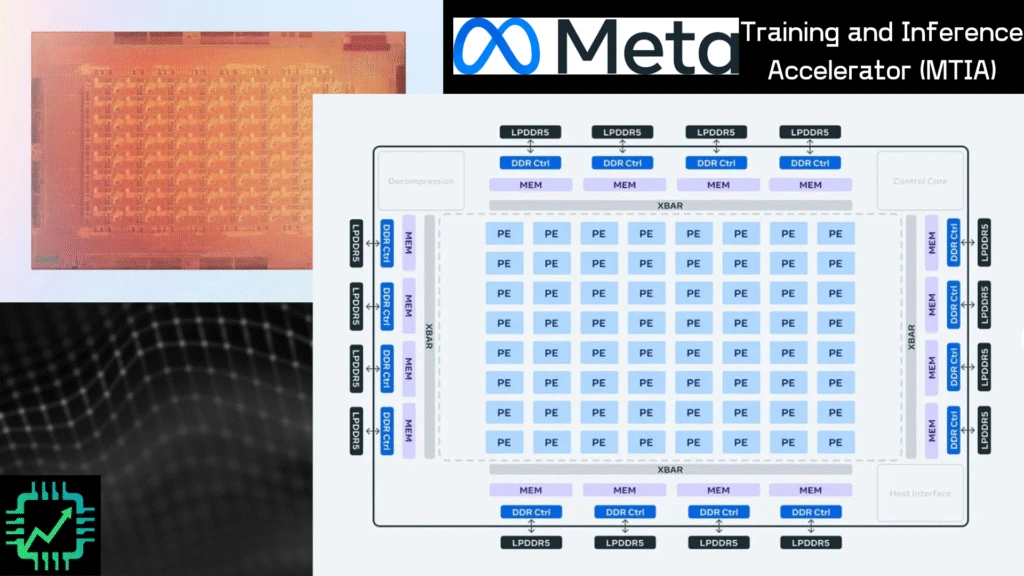

Additionally, much has been said about how Meta and the other hyperscalers have been working on “custom silicon.” We did a write-up (for Semi Insiders) and YouTube video on Meta’s infrastructure, including Meta’s use of its internally developed (likely with Broadcom help, and perhaps Marvell Technology too) MTIA — “Meta Training and Inference” chips — in April 2024. Meta Bets Even Bigger On Nvidia-Powered AI – Meta and NVDA Stock April 2024

What’s all this to do with depreciation risk?

Investing in infrastructure, even though Meta is best known as a social media app and digital ads business, means that there’s some earnings cyclicality investors have to endure. This has been especially the case as Meta’s infrastructure has aged (first data centers built in early 2010s), and computing intensity has increased the last 5 years.

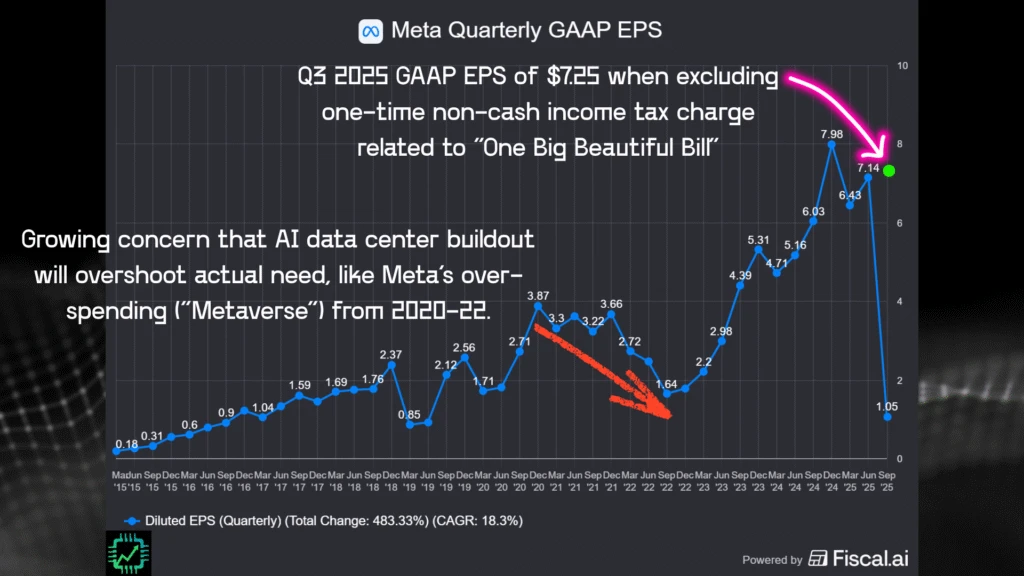

This is the concern raised by Burry and others regarding Meta’s spending on AI data centers and servers. If Meta keeps increasing its capital expenditure (CapEx) spending on AI data centers and GPU servers at the rate it has been this year, earnings per share (EPS) could be headed south like they did in the period from late 2020 through 2022. EPS has already displayed some turbulence as of late. Excluding a non-cash one-time income tax charge related to the implementation of the “One Big Beautiful Bill” in Q3 2025, GAAP EPS was $7.25 — up only 20% YoY, compared to revenue being up 26% YoY. This is a result of expenses — depreciation expense in particular — increasing faster than revenue, and a potential flag for investors to run down.

Want to make financial visuals like the one above for your own analysis? Get 15% any Fiscal.ai paid plan by using our special link — or 25% during their Black Friday sale starting on November 25. Fiscal.ai/csi

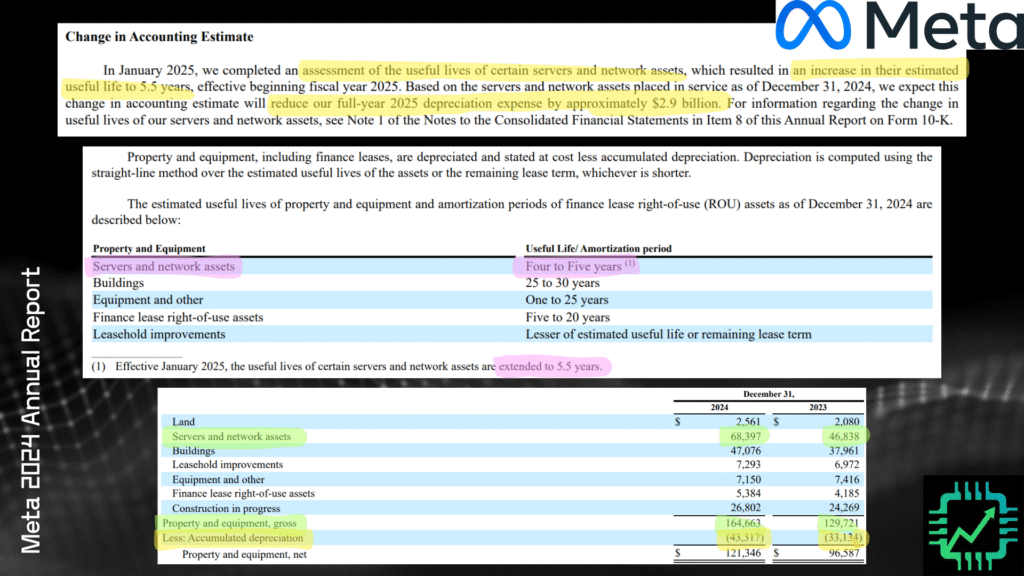

Chip Stock Investor, accounting edition

At the beginning of 2025, Meta increased the expected useful life of certain servers and network assets (GPU-based servers, no doubt) to 5 1/2 years. In prior periods especially starting in 2022, the hyperscalers increased the estimated useful lives of these assets to 4 years, and later to 5 years.

The concern is that Meta has ramped up spending with Nvidia, and because Nvidia is making major new product releases every couple of years, the actual useful life of these assets is in reality much lower than 5 1/2 years. Thus, depreciation is being under-stated, leading to those GAAP EPS in the last slide above being much higher than they actually are.

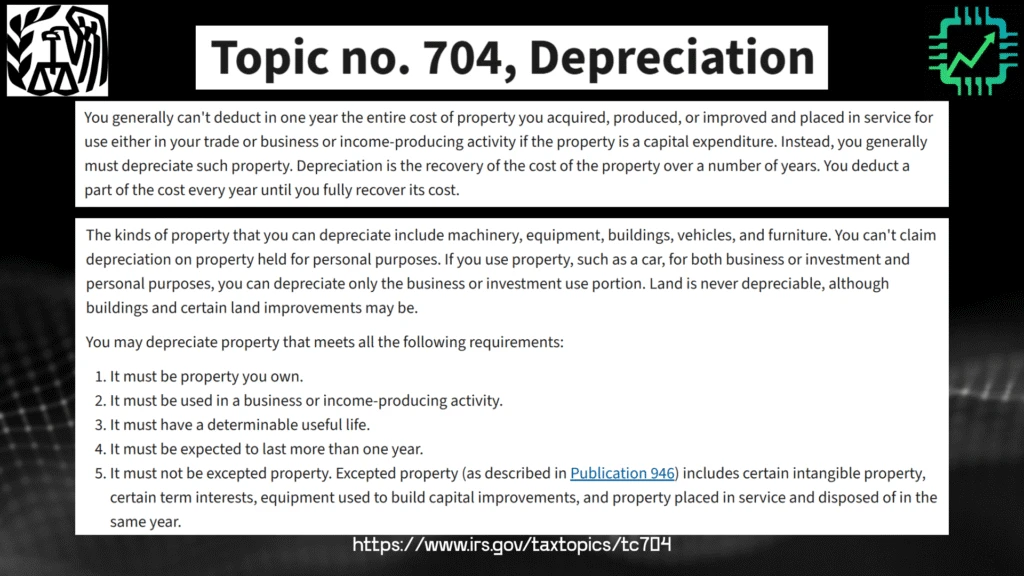

But what is depreciation anyways? Here’s the U.S. IRS (Internal Revenue Service) definition of depreciation.

https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc704

Depreciation is expensing the cost of a long-term asset in “chunks” over the course of multiple years, not all in one year as is typical with short-term assets. Think buildings, computers, vehicles (long-lived assets that help generate revenue) vs. simpler items or services that are expensed one time up front needed in day-to-day business.

Here’s an example of long-term asset depreciation: Let’s imagine Meta spends $5 million on a new Nvidia Blackwell server rack in 2025. Rather than expense the whole amount in 2025 (for tax purposes), Meta will depreciate (expense) the server rack at a rate of about $900,000 in each of the next 5 1/2 years.

The reason for this? The accounting principle involves pairing revenue-generating big-purchase assets with the actual revenue they generate across their life span (when the item needs to be replaced, or needs major maintenance). Essentially, among other things, this encourages steady business investment, as well as provides for steadier tax revenue for Uncle Sam.

Here’s a look at Meta’s long-term depreciable assets (and accumulated depreciation, the total depreciation that a company has recorded for a long-term asset since it was purchased and put into service) as of the end of 2024, the explanation that certain of these assets (some servers and network assets) would now be expensed over 5 1/2 years, and the resulting expected $2.9 billion decrease in depreciation expense for 2025.

Important note: Property and equipment value, and related accumulated depreciation, is removed from a company’s balance sheet when the asset is either disposed of or sold.

Meta 2024 10-K annual report, pages 69, 96, and 107: https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001326801/a8eb8302-b52c-4db5-964f-a2d796c05f4b.pdf

And below in the next slide is the actual $2.29 billion reduction in depreciation expense through the first 9 months of 2025 as a result of the extension of some server useful lives to 5 1/2 years. Also note the big increase in server and network assets, now at nearly half of gross property and equipment listed on the balance sheet.

Server and network asset value increased 46% in 2024, and have increased another 35% through first 9 months of 2025 to $92 billion. Total accumulated depreciation increased 31% in 2024, and has increased another 24% through first 9 months of 2025 to over $53 billion — most of that coming from the rise in AI data center servers from the likes of Nvidia.

The fear is, if these servers are not useful for as long as Meta claims they will be, the company is headed for a big write-down in asset value listed on its balance sheet. Write-downs, especially in the magnitude we’re talking here for Meta (tens of billions of dollars), are detrimental to GAAP EPS.

Meta Q3 2025 10-Q quarterly report, pages 12 and 18: https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001326801/aa3d2e89-2568-4c4c-b3cc-6df47166435e.pdf

But here’s the thing about depreciation…

The real problem with this argument, though, is that depreciation is an accounting method used for tax purposes. It’s measuring the decreasing value of an asset that, in the case of Meta in particular, WAS ALREADY PAID FOR years ago.

As far as we can tell (reviewing the 10-K and 10-Qs, again), Meta isn’t hiding anything in its depreciation and amortization line item on the cash flow statement. While none of the hyperscalers provide a detailed schedule of every long-lived asset and depreciation schedule in their SEC filings (nor does any business, generally), we have heard no reason to believe that GPU servers DON’T last for less than 5 years. After being used for cutting-edge AI R&D for a couple of years, these servers can do more general computing work (including AI inference) for many years thereafter.

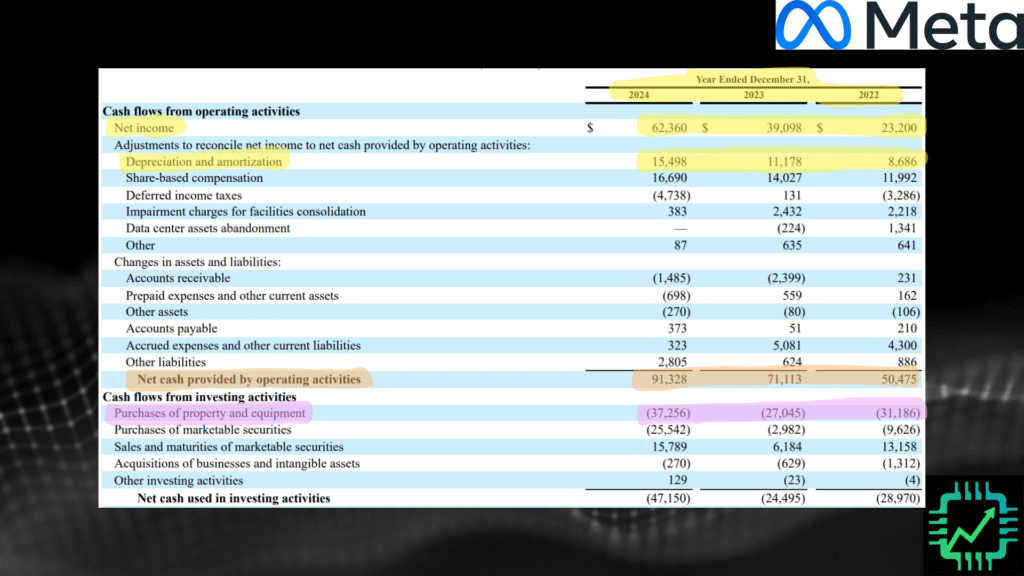

At any rate, here’s the cash flow statement for the full-year periods 2022, 2023, and 2024, as well as the first 9 months of 2025. Note the really big increases in CapEx (purchase of property and equipment, aka. long-lived assets that get depreciated in calculating EPS) the last couple of years. There’s no depreciation risk here. The high CapEx eating into free cash flow is the risk. Free cash flow (FCF) is a non-GAAP metric. FCF is NOT USED in accounting for tax purposes (depreciation is excluded from the calculation. But it’s a really important metric that measures cash left over after operations and CapEx has been paid for. It’s cash available for the company to make further investments with (including acquisitions), to pay off debt, to make stock repurchases, or to pay dividends.

In other words, if you think in terms of owning part of Meta the business, FCF is the profit metric measures the reward your ownership.

Meta 2024 10-K annual report, page 90: https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001326801/a8eb8302-b52c-4db5-964f-a2d796c05f4b.pdf

Meta Q3 2025 10-Q quarterly report, page 10: https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001326801/aa3d2e89-2568-4c4c-b3cc-6df47166435e.pdf

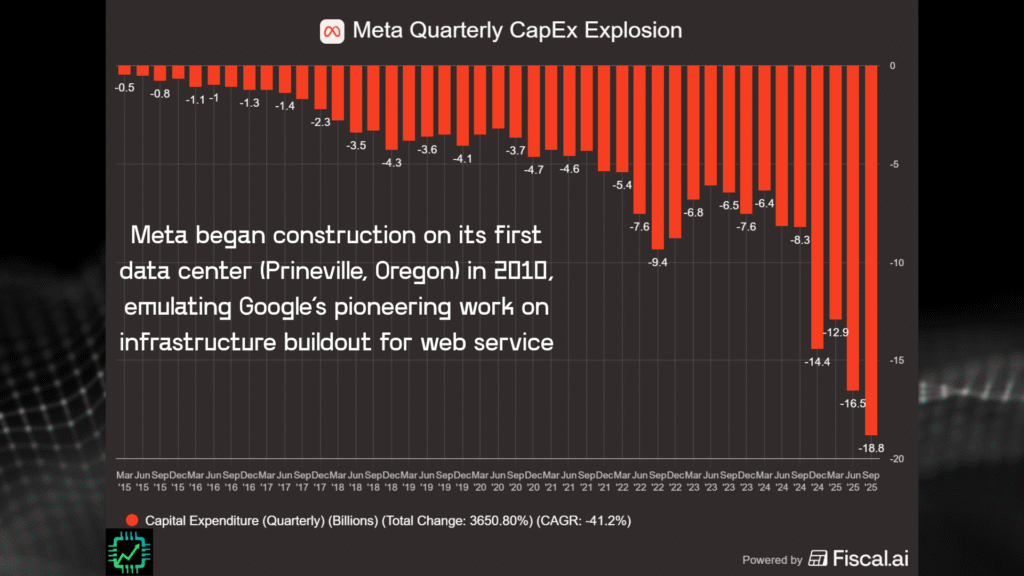

And here’s a closer look at Meta’s quarterly CapEx spend, the amount of money used over and above basic day-to-day operating expenses, on things like AI data centers. The money spent on “certain servers and network assets depreciated over 5 1/2 years” is already gone, so the actual depreciation line item risk is of secondary importance to the CapEx itself. What we really need to be concerned with isn’t the depreciation, but the future profit (or lack of) Meta generates from its purchased data center assets (ROI, or return on investment).

Zuck and co. are out of control again… or are they?

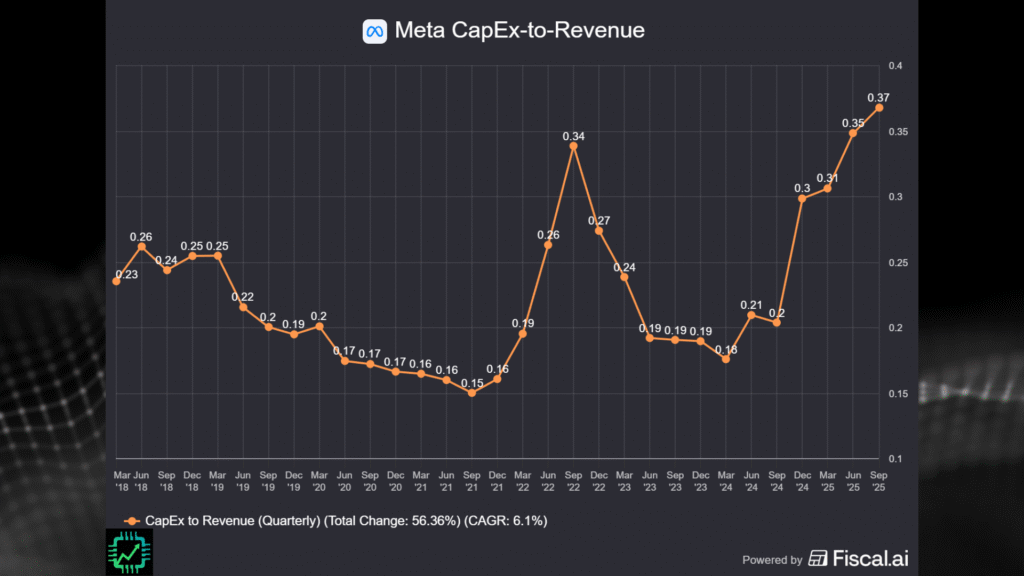

As we have already discussed during Q3 earnings season, below is the measure of Meta’s CapEx-to-revenue ratio (CapEx divided by revenue, the higher the number the more aggressive the spending on long-lived assets like GPU servers), and the Meta CFO quote from the Q3 earnings call. CapEx-to-revenue is a cyclical metric — meaning it ebbs and flows from one year to the next — but it has run particularly high in 2025. This is why the market has sold off Meta stock in November, as the risk of higher CapEx persisting into 2026 needs to be discounted.

“We currently expect 2025 capital expenditures, including principal payments on finance leases, to be in the range of $70 billion to $72 billion, increased from our prior outlook of $66 billion to $72 billion…

…We are still working through our capacity plans for next year, but we expect to invest aggressively to meet these needs, both by building our own infrastructure and contracting with third-party cloud providers. We anticipate this will provide further upward pressure on our CapEx and expense plans next year. As a result, our current expectation is that CapEx dollar growth will be notably larger in 2026 than 2025.”

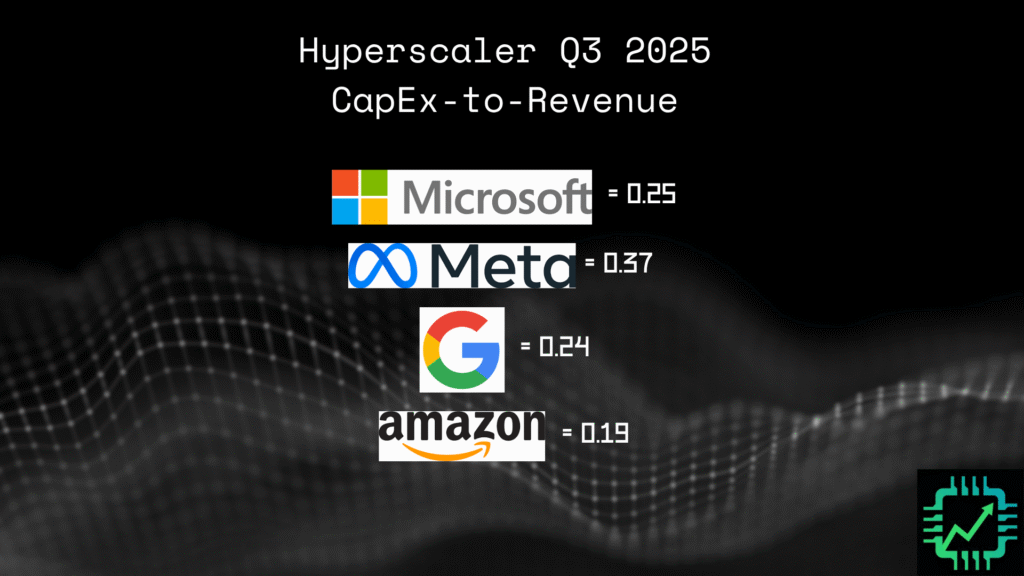

Excluding the neo-clouds (we’ll rank Oracle as a neo-cloud for our purposes here), Meta’s CapEx-to-revenue during this cycle of data center spending is particularly high among the hyperscalers. Microsoft and Alphabet (Google) sit at 0.25 and 0.24, respectively, and Amazon at an almost modest 0.19.

Despite this, though, we need to acknowledge that Meta’s high rate of spend the last couple of years is doing something productive. Revenue has accelerated the last two quarters to north of 20%, and free cash flow is still well into positive territory ($11.2 billion in Q3) despite the elevated CapEx.

Yes, at some point Meta shareholders should expect this CapEx cycle to moderate. It will need to. CapEx-to-revenue cannot remain this high for forever — even if AI (or even AGI, some sort of artificial general intelligence super-app that can automate any computing task imaginible) promises incredible things in the imminent future.

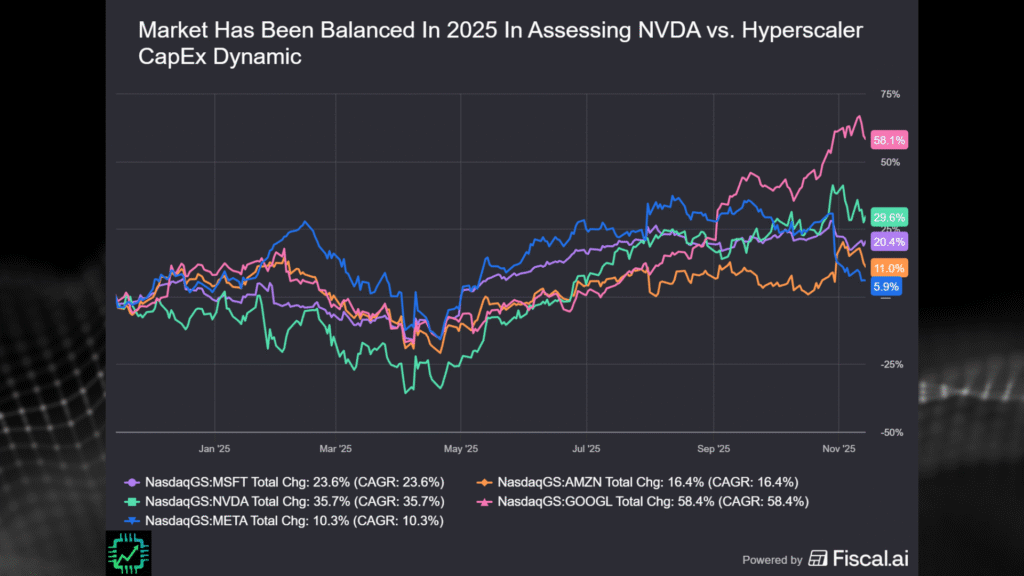

In the meantime, we believe the market is already adjusting for these high rates of spending.

That, friends, is the sign of a healthy market still thinking about inter-company dynamics in a rational way.

See you over on Semi Insider for more of this discussion, including our post-Q3 earnings Nvidia live event and Q&A session.