Much work has been going into breaking down the memory bottleneck to make AI inference (the AI being put to work in software after it’s been trained). A few months ago, we discussed the Nvidia (NVDA) “acqui-hire” of semiconductor design startup Enfabrica. The recent announcement of the Bluefield-4 DPU and Nvidia Inference Context Memory Storage Platform might be (in part) the result of that memory tech licensing. We’ll link our YouTube video on this topic to the top of this article once published.

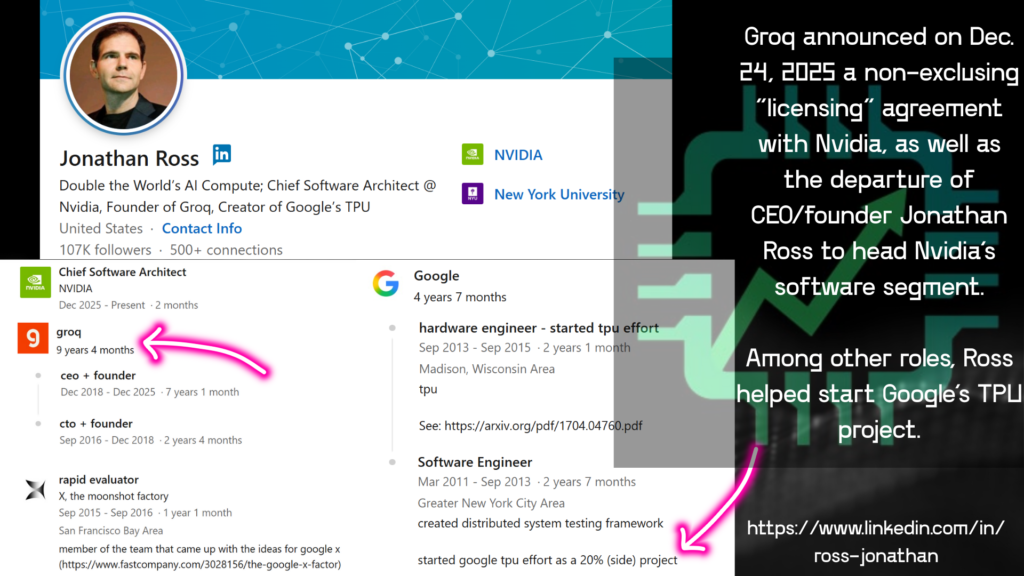

But what about the more recent acqui-hire of semiconductor startup Groq’s CEO/founder Jonathan Ross? Nvidia is on the move, and more AI inference efficiency gains could be on the way.

Back to the “Nvidia is a software company” paradigm

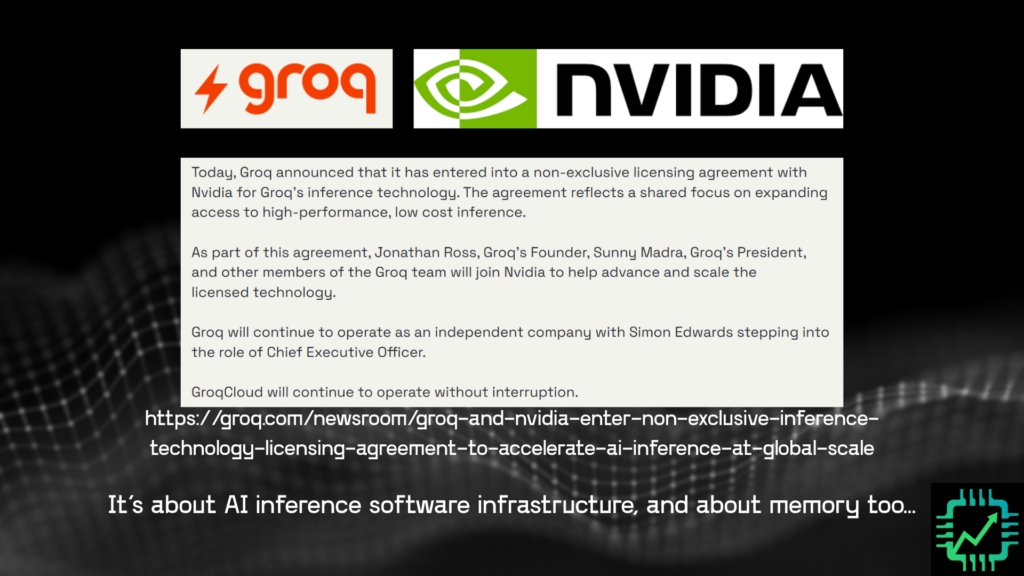

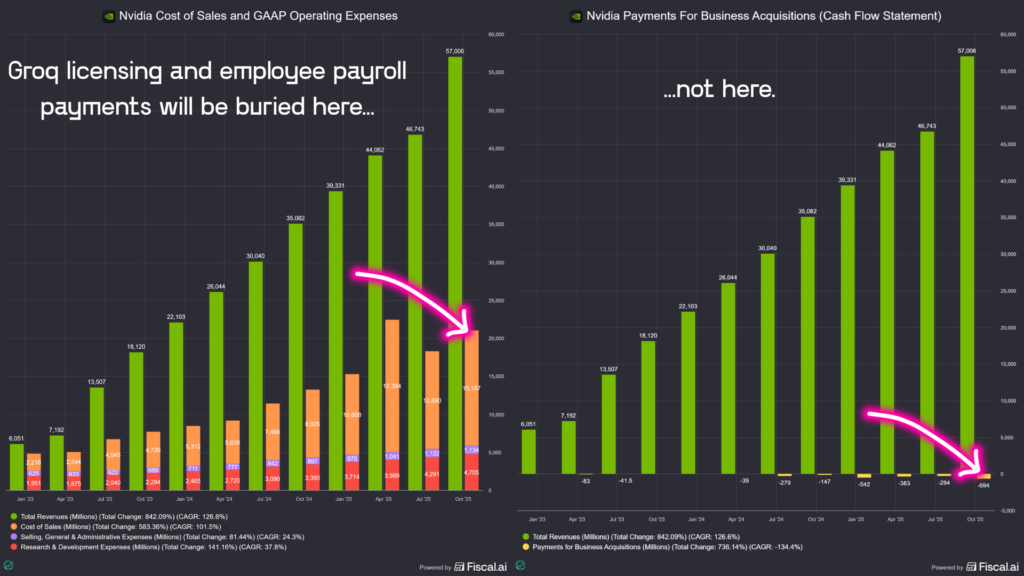

First, let’s acknowledge the rumor (prior to Groq’s announcement) that Nvidia outright acquired the startup for $20 billion. By doing a licensing + employee hire of the top team, Nvidia won’t be shelling out cash up front for an acquisition — and jumping through all the regulatory hoops that might go with it. Instead, expenses will be made on an ongoing basis, and will likely get buried in the GAAP income statement (cost of revenue + operating expenses, which include employee stock-based compensation). We won’t know how much this Groq acqui-hire ultimately costs as a result.

Get tools to do in-depth analysis and make financial visuals like the chart above, and get 15% off any paid plan using our special link: Fiscal.ai/csi/

More importantly, though, why is Nvidia interested in another startup if its systems are already in leadership position for AI inference? For one thing, there’s lot’s of new competition working on making AI inference data center infrastructure more efficient — not the least among them Alphabet‘s (GOOGL/GOOG) Google and its work on the TPU, with help from Broadcom (AVGO). Jonathan Ross, not coincidentally, was involved with getting the TPU project up and running a decade ago.

But when Groq was founded in 2016 by Ross, the hardware design was imagined based first on software need. That has been one of Nvidia’s secrets to success to-date as well.

Yes, of course Nvidia makes money far and away by selling AI data center hardware. But as we’ve been informed for years now, AI is a “full stack problem” spanning chip design, system design, and software infrastructure design. Groq’s boast of being able to deliver faster and more power efficient AI inference compute (validated by Nvidia’s tech licensing deal) is rooted in this same principle.

Groq cites its four design principles as follows (https://groq.com/blog/the-groq-lpu-explained) when it designed its LPU (language processing unit):

- Software-first

- Programmable assembly line architecture

- Deterministic compute and networking

- On-chip memory

The software enables some cool hardware features

As a result of its infrastructure software-driven approach, Groq was able to do some clever hardware work on its LPU — especially in reference to design principle #4 above, on-chip memory.

Specifically, thanks to the way the Groq LPU was designed for AI inference, a lot more real estate could be dedicated to on-chip SRAM (static random-access memory) cells than what’s possible with a GPU. And additionally, while SRAM is usually used for caching in CPUs and GPUs, Groq’s hundreds of megabytes of LPU SRAM instead holds AI model weights. The result is less latency compared to a GPU when it fetches model weights stored in off-chip (but co-packaged) HBM.

Paired with software-based task scheduling that Groq compares to a conveyor belt system that computes a task across hundreds of LPUs working in parallel, that on-chip SRAM (the two dark vertical columns of cells near the middle of the LPU pictured below) helps rapidly speed up inference time and reduce energy consumption compared to AI training GPUs adapted for inference work. https://groq.com/blog/inside-the-lpu-deconstructing-groq-speed

We’ll have to wait and see what new AI inference products Nvidia ultimately ends up designing with the Groq team now under its roof. Some may argue this is an admission by Nvidia that it isn’t up to the task for the “next phase of AI” by making this licensing deal. But really, who in the semi design world is right now? Engineering is all about continuous improvement, and the first rollout was AI training and accelerating existing data center workloads. Inference is different, and now that there’s AI to actually use, everyone is on to the next stage of the race. However you slice it, Nvidia still holds key advantages. And by licensing Groq software-driven design know-how and memory architecture improvements, it’s going to be difficult to dethrone Jensen and co.

See you over on Semi Insider for the full discussion on SRAM, Nvidia’s strategy with Groq, and other AI inference developments in the semiconductor industry.