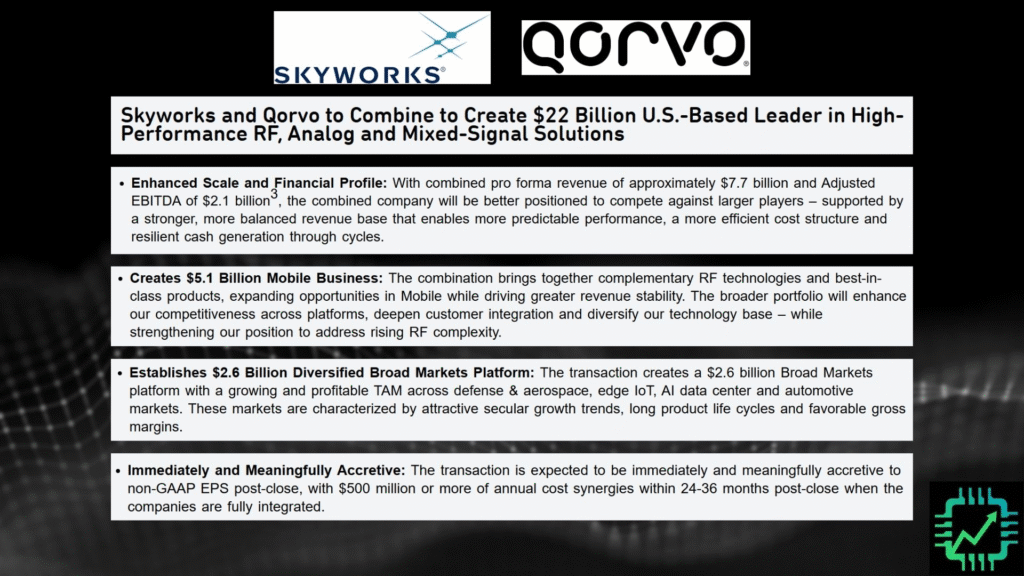

This update is taken from a Semi Insider exclusive write-up regarding the merger recently announced between Skyworks Solutions (SWKS) and Qorvo (QRVO).

- The difficulty of being a big tech (or big anything) supplier

- Relying too much on one customer, or just a few

- How to overcome those challenges and build durable profit growth into the DNA of a supplier company

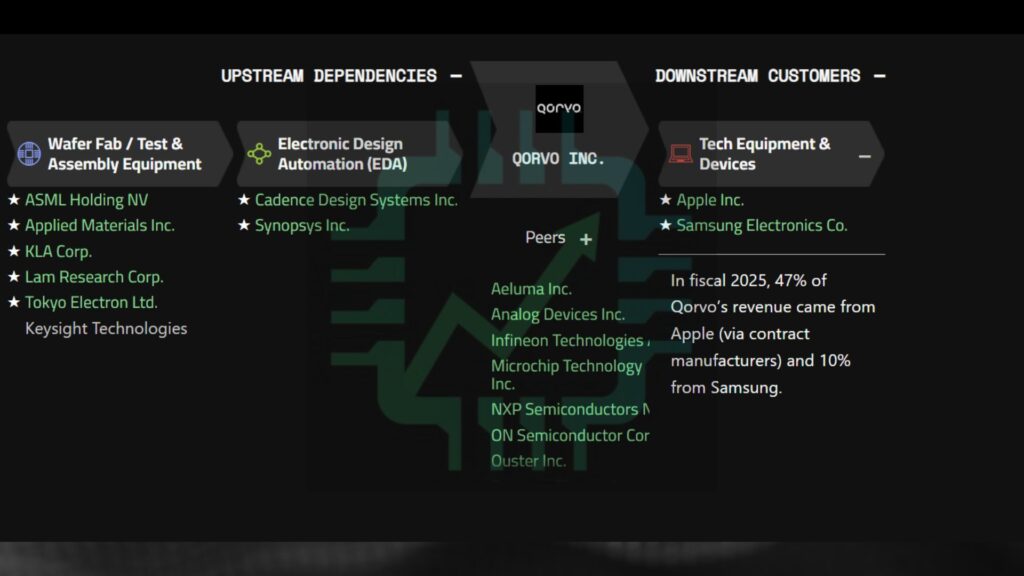

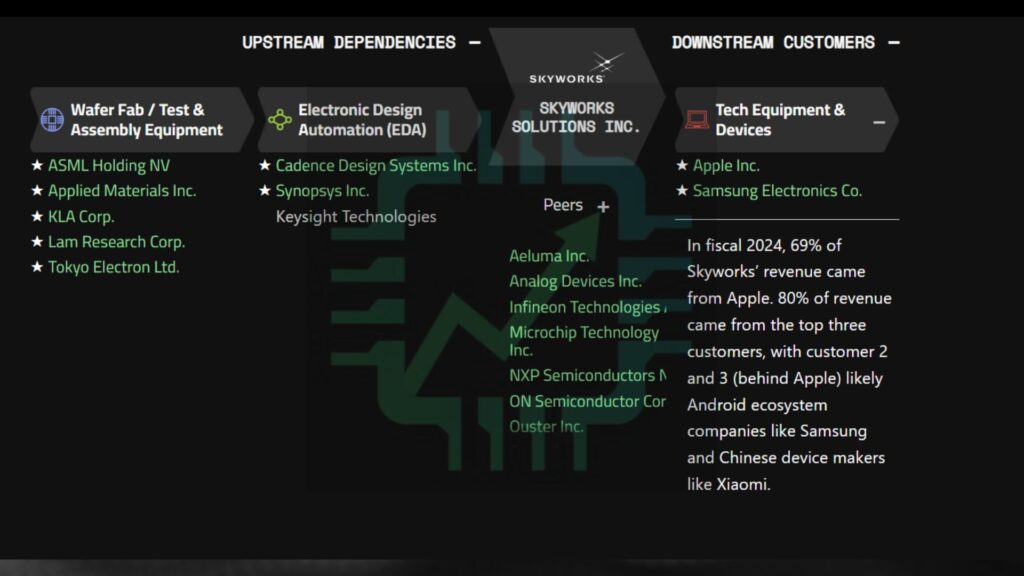

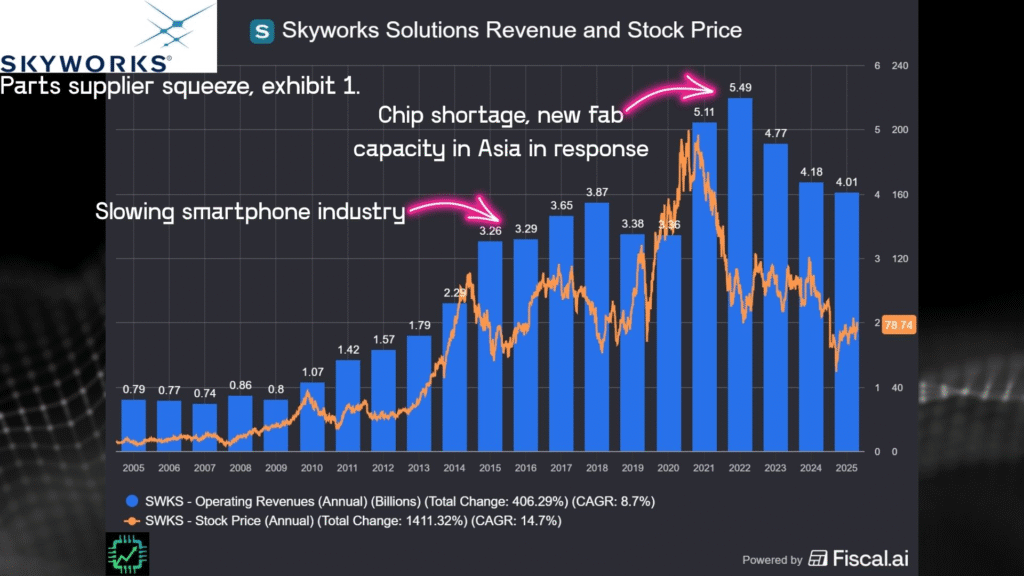

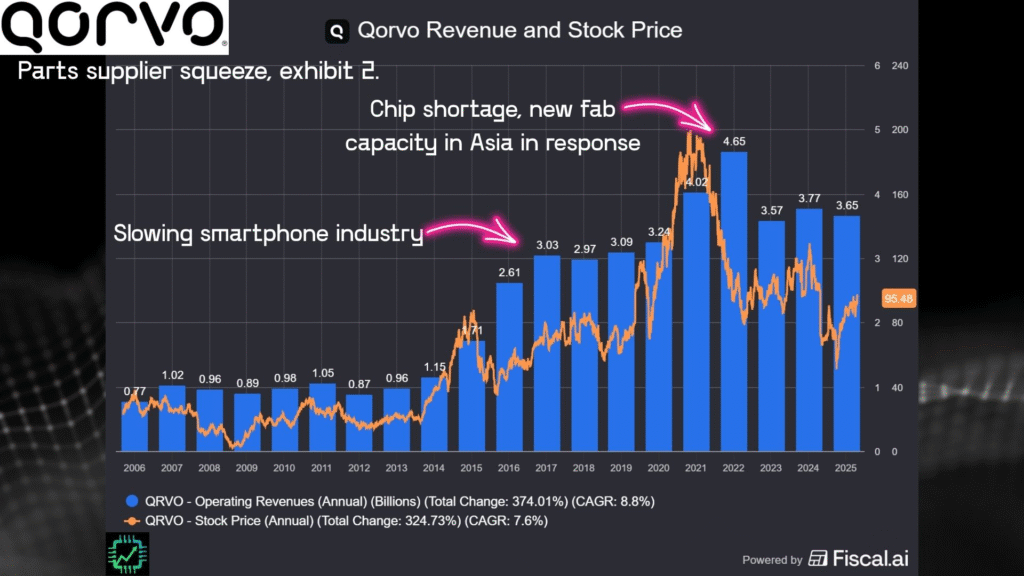

Looking back over the decades, Skyworks and Qorvo have had their moments of greatness. But extreme reliance on Apple (AAPL) has been a high hurdle. (Another overly-iPhone-reliant chip supplier is Cirrus Logic (CRUS), at a whopping nearly-90% of sales from Apple silicon supply.)

Join us on Semi Insider and get early access to our new supply chain analysis tool, revealing key risks, dependencies, and customer relationships for the companies you invest in. chipstockinvestor.com/membership/

Not just an IDM problem

Additionally, global supply chain challenges and geopolitics have made things even worse for two companies looking for that next hit chip product to grow per-share profit again. A Skyworks-Qorvo team up could help return the combined entity (expected deal close of early calendar 2027) to growth.

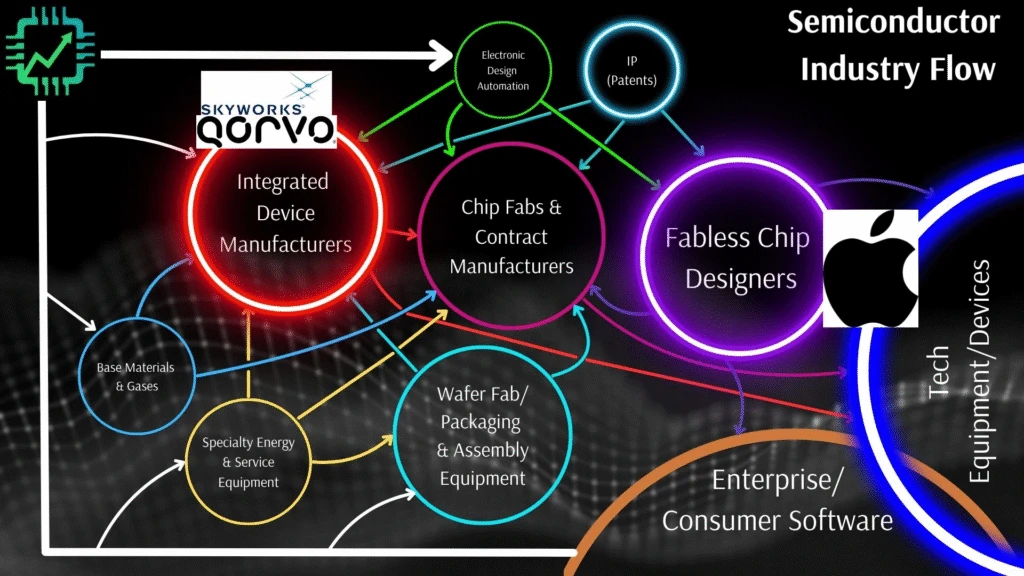

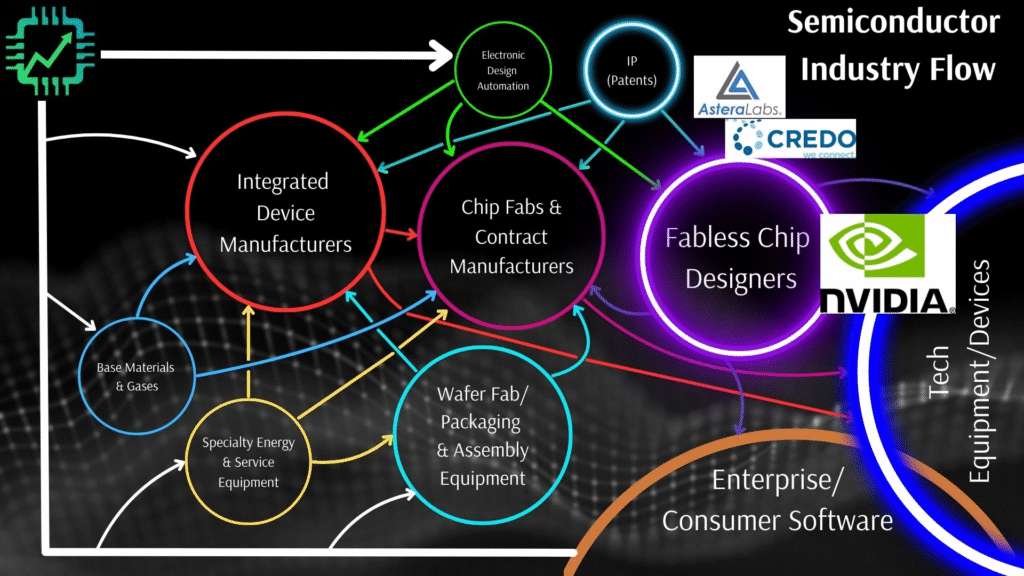

We also need to factor for the struggles of the IDM (integrated device manufacturer, a company that designs and manufactures chips) business model. This became especially evident from effects of the pandemic and the chip shortage that followed through 2022 (What Caused the Chip Shortage?). During that period of unsustainable demand in 2021 and 2022, a lot of new and cheap fab capacity came online, in China in particular, to take some demand from the IDMs. The ensuing downturn that started in late 2022 exacerbated the problem for IDMs like Skyworks and Qorvo.

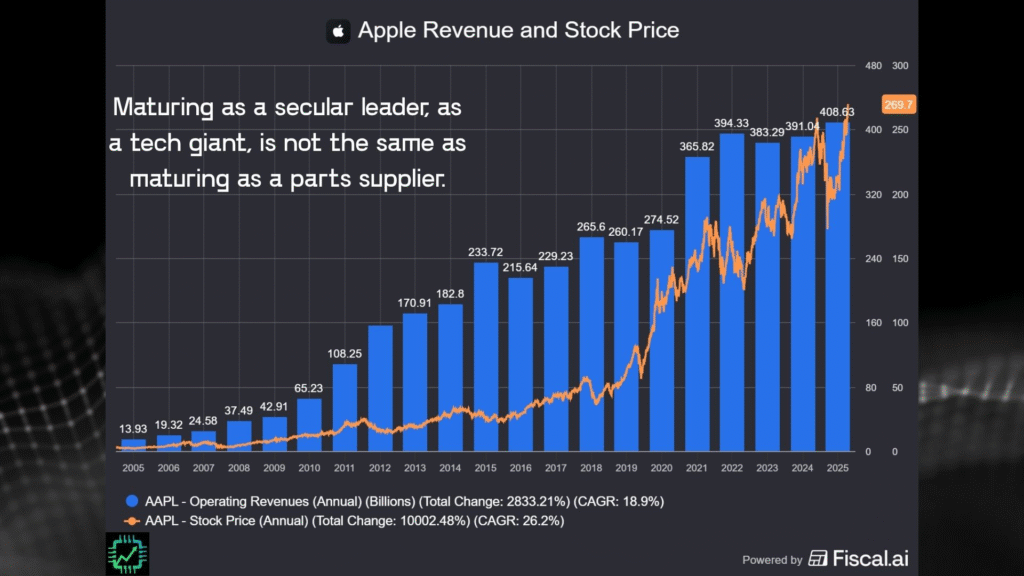

But lets not blame this just on IDM business model woes. Skyworks and Qorvo have been riding Apple’s coattails for years, relying on smartphone and other mobile device growth through much of the 2010s. Apple’s revenue, though cyclical, illustrate the boom that began especially in 2007 with the release of the first iPhone.

During that period, Apple diversified its supplier list, and progressively brought key silicon design in-house (most notably Arm-based processors), to wield control over its costs. The result was a stellar AAPL investment, even as sales growth began to slow in the second half of the 2010s. Buffett and co. certainly did well, even buying AAPL that “late” in the game.

But for the suppliers themselves? Times were good for Skyworks and Qorvo up until about 2015 (Qorvo “growth” in 2016 is the result of merger between RF Micro Devices and TriQuint to create the company known as Qorvo today), up until the effects of Apple’s supply control paired with a maturing mobile market started to bite. Yes, there was that nice lifeline offered by the pandemic and the sales boom following 2020, but sales (and stock price) have reverted back to their doldrum state ever since.

The problem isn’t hard to deduce. Even to this day, Apple accounts for well over 60% of Skyworks’ revenue, and nearly 50% of Qorvo’s revenue. Combining R&D efforts could perhaps help fix the problem, but the onus will remain on a combined Skyworks-Qorvo to deliver growth outside of Apple to its shareholders.

Same story, different industry?

Today, a similar situation is almost certainly shaping up in the AI data center boom. This time, though, instead of an IDM business model, a number of fabless chip designers (outsource manufacturing, predominantly to TSMC) have popped up to ride the AI wave that Nvidia (NVDA) has helped spawn. Hot stocks Astera Labs (ALAB) and Credo Technology (CRDO) embody the situation. (Chip Stock Investor own shares of Credo.)

There are clear similarities here between Apple’s early years of growth, and those of its numerous silicon suppliers. Nvidia is creating fortunes for a new batch of niche chip companies.

How to fight the supplier dilemma

How can companies like Astera and Credo build towards resiliency, and avoid a fate akin to Skyworks-Qorvo years from now? Let’s take a quick look at Broadcom (AVGO)…

Both Broadcom and its merger-initiator Avago (CEO Hock Tan ditched Avago for the apropos name Broadcom at merger in 2016) were serial acquirers in the years leading up to their combination. And post merger, the “new” Broadcom under Tan’s guidance has continued in its highly acquisitive ways.

Active merger and acquisition, that’s the ticket, right? Perhaps Astera and Credo should just merge now and get it over with?

There’s another aspect to this M&A playbook that becomes key, and there’s no guarantee of success unless a company establishes a process for pulling it off. Once an acquisition is made, it needs to be properly integrated into the succeeding business (culture fit, tech fit, sales team product cross-sell capabilities). And then, expenses need to be cut, so-called “synergy” that boosts resulting profit over and above what the two former companies could produce independently.

Both steps are risky, and the acquisition integration process can be upended by cost cutting if a playbook hasn’t been drawn up. Normal industry cyclical downturns also need to be managed during the process — Marvell Technology‘s M&A is an example of how hard it can be. Qorvo too, for that matter, as it not only over-acquired other businesses at the wrong time post-2016 merger, it didn’t ruthlessly cut costs along the way either.

Broadcom, and both entities prior to it, had such a playbook in place. And the shareholder results have been great.

Either way, product and customer diversification is key, paired with diligent control over expenses. The last thing we want, in a decade or so, is to be holding a Skyworks or Qorvo in our portfolio, in need of a merger to combat customer concentration and whatever competitive dynamic will exist in the 2030s. Chop-chop, Astera and Credo.